By: Collin J. Harlan (#9318-1c41)

At the mouth of the River Wear in Sunderland, England, stands a church that has witnessed over 1,350 years of spiritual, intellectual, and cultural transformation. For many, it is a historical site of Anglo-Saxon architecture and heritage. A landmark of early English Christianity and the cornerstone of a once-renowned monastery that helped shape the academic and religious life of medieval England. For the Harlan family, it is not just a place of history, but a place of origin, a physical link to the very location where our earliest known ancestors stepped into history and faith. It is the site where our forefathers, Thomas Harland (born ~1648 AD), George Harlan (born 1650 AD, baptized March 11, 1650 AD), and Michael Harlan (born 1660 AD), were christened in the historic parish church of St. Peter's at Monkwearmouth 1 (Figure 1). I like to imagine their parents standing in awe as their sons received the sacrament of baptism in a church that, even then, was already nearing its first millennium of continuous Christian worship.

The Harlan Family and the St. Peter's Church of Monkwearmouth

Briefly, our family story begins with James Harland, born ~1625 AD in Bishoprick, near Durham, England. A yeoman (landowning farmer) and a devoted member of the Episcopal Church, James lived and died an Englishman 1. In History and Genealogy of the Harlan Family 1, Alphaeus H. Harlan states that "there is no doubt" James Harland was married according to the practices of the Church of England (though we do not know his wife's name).

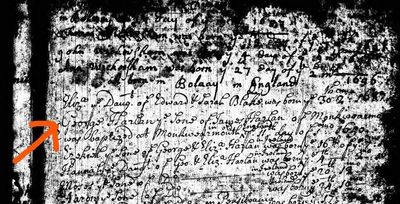

He also notes that James's children were baptized and recorded within the Church. He further states that the earliest known record of James's second son, George, is that he was "baptised at the Monastery Monkwearmouth in Oald England."

This detail is confirmed in a Quaker record from the Kennett Monthly Meeting in Pennsylvania (Figure 2), which indeed documents George Harlan's baptism on March 11, 1650 AD, at Monkwearmouth. This entry, made decades later by George at a meeting of the Religious Society of Friends, reflects one of the earliest documented moments in our family's known history. While it is reasonable to assume that George's brothers were baptized at St. Peter's, and that James and his wife were married there, it is George's sole baptismal record that provides us with a direct and recorded link to this historic church.

Like his father and brothers, George was raised in the Episcopal faith. But in adulthood, the three brothers embraced Quakerism, a decision that would shape the rest of their lives. To escape religious persecution, the Harlan brothers immigrated to Ireland, where they joined a growing Quaker community and, in 1678 AD, George married Elizabeth Duck by ceremony of Friends in County Down, Northern Ireland. In 1687 AD, George, Elizabeth, and their children, along with Michael, sailed to Pennsylvania, seeking the religious freedom promised by William Penn 1, 2.

But before America, Ireland, and the Quakers, George and his brothers began life as English children, brought into the Christian faith at one of the oldest and most historically significant parish churches in Britain.

Monkwearmouth: A Center of English Christianity and Learning

St. Peter's Church in Monkwearmouth was founded in 674 AD by Benedict Biscop (Figure 3), a Northumbrian noble, Roman traveler, and visionary churchman, after he recieved a royal land grant from King Ecgfrith of Northumbria 3, 4, 6.

Biscop had journeyed to Rome multiple times, returning with relics, manuscripts, and skilled artisans from Gaul (modern France, and parts of Belgium, Luxembourg, Switzerland, northern Italy, and western Germany) to help construct a church in the Roman style. Modeled on continental ideals (traditions from mainland Europe), the monastery introduced stone construction, glass windows, and Roman liturgical practices to England for the first time. Biscop's goal was to establish a center of religious learning and worship that would elevate English Christianity both spiritually and intellectually. Alongside its sister site, St. Paul's Church at Jarrow, established in 681 AD, the two formed a "double monastery" that became one of the most important centers of learning in Europe during the 7th and 8th centuries. As Benedict Biscop believed, "The house of God is the school of learning," and St. Peter's in Monkwearmouth and St. Paul's in Jarrow were built to reflect that vision.

It was also here that Bede the Venerable (Figure 4), one of the greatest scholars of the early Middle Ages, lived, studied, and wrote his Ecclesiastical History of the English People, a monumental work that earned him the title "Father of English History"4, 5. Bede was brought to the monastery at 7 years old in 680 AD, only years after St. Peter's was founded, and remained a monk at Wearmouth–Jarrow for life. His writings covered theology, science, chronology, biblical interpretation, and education, helping to preserve and transmit classical and Christian knowledge throughout early medieval Europe. Bede was also the first to use the term Anno Domini (AD) to date historical events, a system still in use today (in the spirit of St. Bede, I have placed AD after all dates used in this article). In 1899 AD, Pope Leo XIII declared Bede a Doctor of the Church, an honor reserved for saints whose scholarly or theological contributions have had a lasting influence on Christian teaching.

During the period of Bede, the Wearmouth–Jarrow scriptorium produced three colossal single-volume Bibles, modeled on the Codex Grandior, a manuscript that Benedict Biscop had brought back from Italy. These massive volumes, called pandects, were created between 700 and 716 AD under the leadership of Abbot Ceolfrith, Biscop's right-hand man. Two of the Bibles remained at the monasteries of Wearmouth and Jarrow, while the third was intended as a gift for Pope Gregory II. Abbot Ceolfrith set out for Rome in 716 AD to deliver it personally, but he died en route in Gaul. Although the Bible never reached the pope, it was found and preserved in a monastery in Tuscany. Today, this volume is known as the Codex Amiatinus and is recognized as the oldest complete Latin Vulgate Bible in existence. It is housed in the Laurentian Library in Florence, and scholars believe it includes annotations and corrections made by Bede himself.

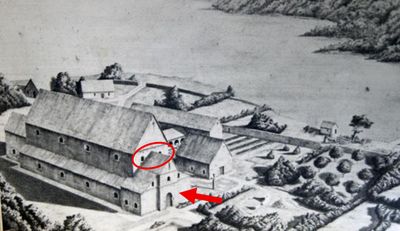

By the early 8th century, the combined monasteries of Wearmouth (Figure 5) and Jarrow housed over 600 monks, producing illuminated manuscripts, biblical translations, and foundational works of English history. In many ways, the twin monasteries were the Cambridge and Oxford University of their time, serving as a beacon of scholarship, literacy, and cultural preservation in early medieval England 3, 4, 6.

Monastic Glory, Viking Destruction, and Rebirth

Unfortunately, over the centuries, the Wearmouth–Jarrow monastery endured waves of destruction and fires. The first major blow came in 794 AD, when Danish Vikings raided the monastery at Jarrow, killing monks and looting sacred relics. A second attack in Monkwearmouth followed around 798 AD, leaving the buildings of St. Peter's damaged and the monastic community scattered 6. These assaults marked the beginning of Viking incursions into the Kingdom of Northumbria, and although some rebuilding occurred in the following decades, the twin monasteries never regained their former prominence. By the 9th century, they had largely fallen into decline, and much of their scholarly activity ceased.

Following the Norman Conquest, William the Conqueror ordered the monastery restored 6. In the 11th century, it was revived as a Benedictine chapter under the Abbey of Durham. Later centuries saw Monkwearmouth become a simple and quiet English parish church, though its walls still echoed with the weight of history.

I can't help but wonder when the Harlans first came to Monkwearmouth, and how deep the connection between St. Peter's Church and the Harlan family runs. How many baptisms, weddings, and funerals might have taken place there for our ancestors prior to James Harland? Though we may never know for certain, the record of George's baptism in 1650 AD forever ties our family to the enduring legacy of Saint Bede, Benedict Biscop, and St. Peter's monastic origins 1, 3, 6.

Anglo-Saxon Architecture: A Living Monument

St. Peter's Church still preserves several remarkable examples of its original Anglo-Saxon architecture. The west wall (Figure 6), constructed in 674 AD, is the only surviving part of the original church built under Benedict Biscop, and it remains a rare and invaluable link to England's early Christian era 3, 6. The quality and strength of the Anglo-Saxon mortar used during construction of the original monastery is the reason the west wall of the church is still standing. Anglo-Saxon mortar hardened with age and was similar in mixture and average particle size to mortar used today 8. Additionally, the decorative door arch, carved stonework, and even fragments of stained glass, all revolutionary features at the time, remain as some of the earliest surviving examples of stone ecclesiastical architecture in England.

These elements weren't just artistic flourishes. They were intentional efforts by Benedict Biscop to model English Christianity on the continental church, importing not just theology, but culture, art, and scholarship 4. The church was one of the first buildings in England to incorporate glass windows, and it housed one of the greatest libraries in Europe at the time, enabling Bede and others to preserve and transmit knowledge that helped shape Western civilization4, 5.

Legacy, Loss, and the Fire of 1790

Tragically, in 1790 AD, a fire consumed many of St. Peter's Church's ancient parish records 6. Among those destroyed were baptismal, wedding, and burial registers, likely including the original documentation of Thomas, George, and Michael's baptisms and James Harland's wedding. The fire most likely erased all existing records of the Harland family prior to James, a devastating loss of history for our family. According to church records, the fire broke out in the early morning hours of April 12, 1790 AD, in the residence of Reverend Jonathan Ivison, the minister of Monkwearmouth at the time. It is believed that an overturned candle caused the blaze, which not only destroyed the home and its contents but also the church's ancient records stored within. The tragic event weighed heavily on Reverend Ivison, who died two years later in 1792 AD.

Though the monastery is long gone and much of the original church has been lost to time, St. Peters Church still stands as a living monument. The original Anglo-Saxon stones of the west wall endure not just as architectural marvels, but as witnesses to English history. They have seen centuries of faith and conflict, ruin and rebirth. They stood as Saint Bede passed through them, and centuries later, they stood as James Harland and his wife entered with their sons for their baptism (Figure 7).

A Family Connection to a Monument of History

On May 27, 2025 AD, several members of the Harlan Family in America made a pilgrimage to Monkwearmouth (Figure 8) in Sunderland, England. We, too, passed through the same stones of St. Peter's west wall that our ancestors did over 350 years ago, and in doing so, we made a connection across oceans and generations to the sacred place where the story of the Harlan family begins.

Our family connection to St. Peter's in Monkwearmouth, once a central institution of early English Christianity and currently an operating parish, reflects a documented link to one of the oldest parish churches in Britain. It is a point of origin that anchors our family history in a place of national significance. What an incredible thing to be proud of and excited about!

As Harlan descendants, we carry with us not just a name, but a legacy rooted in one of the most historic churches in England. Monkwearmouth reminds us that our story didn't begin in America, or even in Ireland, but in a sacred stone building by the mouth of the Wear River, in a land once called Northumbria, where saints walked, and English history was written.

References

-

Harlan, Alpheus. History and Genealogy of the Harlan Family. Baltimore: The Lord Baltimore Press, 1914.

Includes detailed genealogical records of James Harland and his sons Thomas, George, and Michael, as well as their migration from England to Ireland and later to Pennsylvania. -

"George Harland/Harlan (1650–1714), Quaker, Immigrant, Farmer, Father." Just A Harland Chasing My Family Tree (Blog), January 2020. https://jahcmft.blogspot.com/2020/01/george-harlandharlan-1650-1714-quaker.html

A personal genealogical summary placing George Harlan in the broader context of 17th- century Quaker migration and religious history. -

"St Peter's Church, Monkwearmouth." Wikipedia, last modified 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St_Peter%27s_Church,_Monkwearmouth

Overview of the church's historical, architectural, and religious significance from its founding to modern restoration. -

"Benedict Biscop." Wikipedia, last modified 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Benedict_Biscop

Biography of the church founder, his travels to Rome, role in establishing a center of learning, and architectural innovations at Monkwearmouth-Jarrow.

-

"Bede." Wikipedia, last modified 2024\. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bede

In-depth account of the Venerable Bede's life, works, contributions to Christian historiography, and legacy as one of medieval Europe's most influential scholars. -

"Monkwearmouth and Its Records." Durham Records Online Library. https://durhamrecordsonline.com/library/monkwearmouth-and-its-records/

Historical narrative describing Monkwearmouth parish life, Viking and Norman invasions, the 1790 fire, and later administrative integration into Sunderland. -

"St Peter's Church, Monkwearmouth," Great English Churches, https://www.greatenglishchurches.co.uk/html/monkwearmouth.html

Detailed architectural and historical overview of St. Peter's Church, highlighting its Anglo- Saxon features, restoration efforts, and significance within the broader context of English ecclesiastical heritage. -

Points, Guy. Anglo-Saxon Church Architecture & Stone Sculpture. Great Britian: Rhitspell Publishing, 2023.

A book for readers who wish to learn more about Anglo-Saxon church architecture and stone sculpture. Photos and mentions of Monkwearmouth are featured throughout.

Additional Reading

-

Monkwearmouth Anglo-Saxon Monastery and Medieval Priory

Historic England – Official heritage listing describing the historical significance, architectural features, and protected status of the Monkwearmouth site. -

Parish of Monkwearmouth

Monkwearmouth CofE – The parish website offering contemporary insights, service information, and a brief history of St. Peter's Church. -

National Churches Trust

National Churches Trust – A preservation-focused overview of St. Peter's, highlighting its heritage importance and restoration needs.

-

Doc Brown's Monkwearmouth Tour

Doc Brown Info – A photographic tour with captions providing visual context and brief historical commentary on Monkwearmouth.

-

History of St. Paul's at Jarrow

English Heritage – A detailed history of St. Peter's sister monastery at Jarrow, illuminating the dual-monastery model founded by Biscop and Ceolfrith. -

Inside Anglo-Saxon Church Architecture and Stone Sculpture

Script Books Blog – A blog post exploring Anglo-Saxon stonework and church design, with references to Monkwearmouth's surviving architectural elements by Guy Points. -

Patricia Lovett's Monkwearmouth Tour

Patricia Lovett: Monkwearmouth – Reflections by a professional calligrapher and heritage specialist on the spiritual and artistic significance of St. Peter's Church and its medieval legacy.